Fetal imaging

Prenatal imaging errors : How do we explain them?

Prenatal imaging has developed for several decades and technological advances have continued to mark its path. However, on a daily basis, pediatricians, especially those who work in maternity hospitals, are led to notice errors in prenatal imaging. These errors can be venial, with little consequence for the patient, or unfortunately much more dramatic.

These errors, why do we make them, what difficulties do we encounter in our daily practice that can explain them? Can we avoid them? The purpose of this article is to answer these questions and illustrate them in two cases.

For starters, a brief mention should be made of the major recent advances in prenatal imaging, both technologically and in working conditions.

Over the past decade, technological advances have focused on the development of new probes improving spatial and contrast resolution, the development of 3D and 4D imaging, and harmonic imaging.

Therefore, in the case of a dispute concerning an old case, it is always important to be placed in the technical context of the time at the time of the facts. Working conditions in prenatal imaging have also changed with the establishment of multidisciplinary prenatal diagnosis centers (CPDPN). This has resulted in the break-up of the isolation of practitioners who are, in principle, all connected to a network and can more easily appeal to a colleague in case of doubt on an ultrasound image. In addition, a decade ago the National Technical Committee on Antenatal Screening ultrasound was established, which only allows doctors and midwives to perform ultrasound tests and advises on the practice of 3 systematic examinations for the first (11-13 SA + 6 days), second (20-25 SA) and third (30-35 SA) quarters. It is interesting to clarify this concept of screening.

Screening ultrasound

The purpose of screening ultrasound is to identify in a safe population fetal abnormalities that are at high risk of perinatal mortality or require specific perinatal care.

According to the recommendations of the National Technical Committee on Antenatal Screening Ultrasound (CNTEDA)(1), it is clear that such a review cannot identify all potentially recognizable anomalies. Thus, only a limited but clearly defined number of anatomical structures must be studied.

It is therefore proposed that a standardized image be made that includes cuts imposed on different regions of the body.

The structure of the report to be produced is also proposed. In addition, quality control is recommended with regard to operator training and equipment used. Understanding this concept of screening is very important. This practice is dangerous because it calls for extreme vigilance in order to isolate the problem within a mass of normal examinations.

So how do I define an error ? For example, for a pediatrician who finds that a newborn has a posterior palatine slit and an undiagnosed retrognathism in prenatal periods, it is tempting to refer to a "misdiagnosis". In fact, the study of the posterior palace and the study of the fetal profile are not recommended for screening. Why ?

On the one hand, because the screening of posterior palate slices is technically difficult and, on the other hand, because the Technical Committee feared that the systematic screening of fetal profile anomalies would lead to an excess of false abnormal examinations. The consequences of these "false positives" of screening can be severe: miscarriages related to unnecessary amniocentesis, mother-to-child disorders, requests for termination of pregnancy, etc. What happens when a structure to be tested has been considered normal when it actually presents an anomaly? Is this an inevitable error or false negative of screening? It is difficult to answer for each case. It should be recalled that the study of malformation registers(2) shows that the vast majority of abnormalities cannot be detected in 100% of cases, but that there are large differences in sensitivity in different regions of Europe, suggesting a variable quality of examinations. However, it is now possible to clarify whether the screening examination was in compliance with the recommendations. It’s easy for reporting and number of shots. This is difficult for a given cliché, because expert opinions are often discordant.

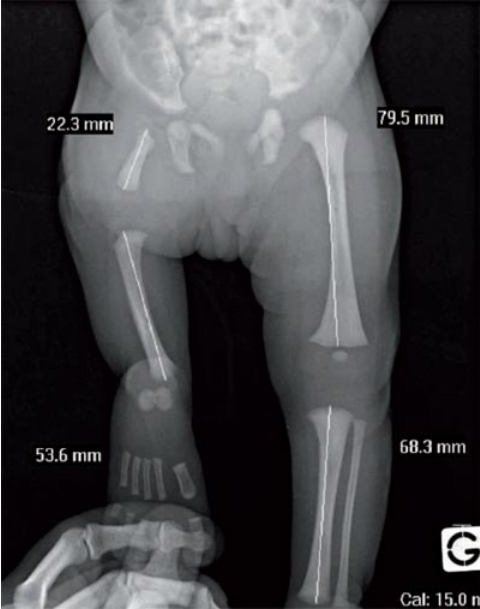

Figure 1 illustrates a default error case leading to an erroneous conclusion of normality.

Figure 1: A child born from a well-followed pregnancy, with three ultrasound tests known as normal. The front lower limb radiography at birth shows a congenital short femur on the right. In this case, there is a real error, since the three segments of each member must be visualized during a screening ultrasound. While their measure is not recommended, such a shortening of a member segment should have been diagnosed. It is likely that only the left femur was visualized in the various prenatal ultrasound.

Diagnostic ultrasound

This is a second-line ultrasound performed in response to a high risk of fetal morphological abnormality or following a screening examination that identified an abnormality or was performed under technical conditions that would not permit a conclusion. More recently, the same CNTEDA made recommendations for diagnostic ultrasound(3) and proposed, as had already been done for screening ultrasound, a methodology for ultrasonists performing this type of examination.

This list lists the various elements to be examined, the structure of the report, the images and the biometries to be produced.

Other Imaging Examinations

● Fetal Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) began to develop in France in the 1990s. Initially centered on the study of the fetal brain, which remains by far its main field of investigation, MRI also allows to study other anatomical organs or regions, such as the lung, digestive tract, pelvis or neck. An abundant literature on this subject has emerged, analyzing, among other things, the contribution of this technique to ultrasound, its diagnostic efficacy and the technical problems it creates.

It requires, in order to be effective, practicing by a trained operator, knowledgeable of the fetal pathology and the normal aspects of the different organs during development. There are many traps(4). This technique is dependent on the operator as is any other medical examination and it is not recommended that such an examination be carried out only after multidisciplinary consultation.

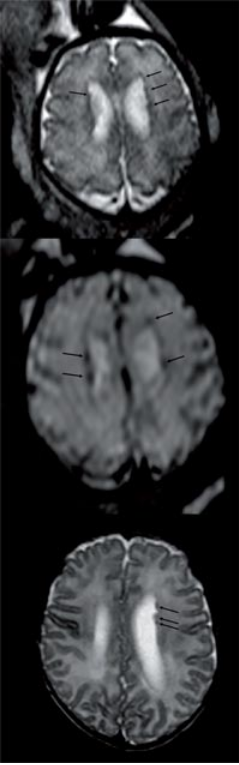

Figure 2 illustrates the difficulties encountered in interpreting fetal MRI images.

● Fetal tomodensitometry is an even more confidential examination, carried out sparingly in the CPDPNs according to a very precise protocol to limit to the maximum the dose of irradiation given to the fetus and in very precise indications, mainly in cases of bone abnormalities which may or may not be part of a constitutional bone disease.

Figure 2: Fetal MRI performed at 33 SA due to bilateral ultrasound ventricular dilation measured at 14 mm at each ventricular junction. On the T2 (a) and T2* (b) axial sections, passing through the upper side ventricles, there are a few small hypo-intense images, more marked in T2* and interpreted as hemorrhage causing ventricular dilation. On postnatal control, 1 month of life (c), we see that these images actually correspond to small subdependent heterotopies.

How do we explain our mistakes?

Whether false positives or false negatives, there are several sources of errors.

◦ Technical Errors

This may be the inappropriate choice of an ultrasound probe or an MRI sequence that will not identify a lesion. For example, the visibility of a chronic MRI bleeding can only appear obvious with one type of sequence. This sequence must also be considered. It can also be the misinterpretation of an image linked to the fact that it was not acquired in a correct plane and that the anatomy is therefore not recognizable. So we can build false pathologies. This can also be an error in the measurement process, leading to errors in the estimation of fetal weight. Interobserver variability is greater for perimeter measurements than for linear measurements(5).

◦ Problems related to examination

These are very common in prenatal imaging, whether it be problems related to oligoamnios, fetal presentation or maternal wall in ultrasound, or fetal movements in MRI. These errors can also be related to the psychological state of the operator, a decrease in vigilance due to overwork. An abnormal image may thus be incorrectly trivialized or missed.

◦ Errors related to operator insufficiency

They are also very common because of the vast scope of knowledge to be acquired. The same person cannot know all the variants of the normal and all the pathologies of the different organs that may be revealed in utero.

How do I reduce the risk of errors?

The recommendations of the CNTEDA defined a quality assurance process: adapted equipment, initial and continuing training of professionals, and regular and sufficient practice. The quality of this training is the best guarantee of the effectiveness of screening(6). In France, initial training is structured by IUDs, continuing training is provided by several organizations, such as the French College of Fetal Ultrasound, and this contributes greatly to the good sensitivity of ultrasound screening in our country(7). There is still the problem of overwork and less vigilance due to the excessive number of examinations carried out. It was suggested that this should be corrected by taking breaks in the day(8). The current rating of the acts remains a major problem(3), since the remuneration of the screening ultrasound is too low, while it is a long and difficult examination, which forces some colleagues in sector 1 to multiply the examinations.

Conclusion

In practice, prenatal imaging is thus a dangerous exercise, with the risk of false positives and false negatives like any other medical examination. The quality assurance procedures recommended for several years should help improve the performance of screening. This is an important objective, as mismatches between prenatal and postnatal diagnosis can have serious consequences.

However, it should be borne in mind that prenatal imaging has limitations and that even in the best hands and with good technique, some malformations remain unapparent.

1. www.ladocumentationfrancaise.fr/rapports-publics/054000356/. Rapport du Comité national technique de l'échographie de dépistage, avril 2005.

2. www.eurocat-network.eu

3. www.cngof.asso.fr/D_TELE/100513_rapport_echo.pdf. Rapport du Comité national technique de l'échographie de dépistage, mars 2010.

References

Click on the references and access the Abstracts on

4. Al-Mukhtar A et al. Diagnostic pitfalls in fetal brain MRI. Semin Perinatol 2009 ; 33 : 251-8. Search the abstract5. Dupley NJ. A systematic review of the ultrasound estimation of fetal weight. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2005 ; 25 : 80-9. Search the abstract6. Levi S. Ultrasound in prenatal diagnosis: polemics around routine ultrasound screening for second trimester fetal malformations. Prenat Diagn 2002 ; 22 : 286-95. Search the abstract7. Garne E et al. Prenatal diagnosis of severe structural congenital malformations in Europe. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2005 ; 25 : 6-11. Search the abstract8. Tabor A et al. Screening for congenital malformations by ultrasonography in the general population of pregnant women: factors affecting the efficacy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2003 ; 82(12) : 1092-8. Search the abstract